- Home

- Ctrl B (retail) (epub)

Ctrl + B Page 21

Ctrl + B Read online

Page 21

“So have you been enjoying India?” my uncle asked in English tangled like seaweed, four hours into the trip.

“Oh, yeah. It’s been really great being back but a little hard adjusting, you know?” A drop of sweat clung to the end of my nose.

He answered with silence and a wormy smile, which I took as encouragement. But when we reached Shimoga, he told my cousin in Kannada, “I couldn’t understand a word.” At dinner that night, I stared at my hands and didn’t speak.

Meals were the hardest. My grandmother would hand me the only fork and plate in the house while she used her hands and ate off banana leaves. I fidgeted in knobby wooden chairs and couldn’t figure out what to do with my elbows. The milk for my cereal was warm and lumpy.

I would eat most breakfasts with my great-aunt staring at me from across the table. I read a newspaper, getting milk in my hair. Before I left India she said, “I like your mother. She’s better company.” I pretended not to understand.

When I returned home to New York, I signed up for Kannada classes. In three weeks I learned the basics: what I wanted to eat for dinner and that I needed to use the bathroom. Four years later I returned to India and had a conversation with my grandmother for the first time. It was slow and halting, but it worked. I had learned.

SIMERA LADSON

YEARS AS MENTEE: 1

GRADE: Senior

HIGH SCHOOL: Edward R. Murrow High School

BORN: Brooklyn, NY

LIVES: Brooklyn, NY

PUBLICATIONS AND RECOGNITIONS: Scholastic Art & Writing Awards: Gold Key, Honorable Mention; published in The Magnet (2015–2019)

MENTEE’S ANECDOTE: Every time I’m with Caroline I have a good time. She pushes me to try new things in my writing, and I always leave our sessions feeling a little more accomplished than I had when I walked in.

CAROLINE SYDNEY

YEARS AS MENTOR: 1

OCCUPATION: Editorial Assistant, Penguin Random House

BORN: Dallas, TX

LIVES: Brooklyn, NY

MENTOR’S ANECDOTE: In our relationship, Simera definitely comes to our sessions as a writer and I as an editor. Over the course of this year, I’ve most enjoyed the way that we push each other into the less-familiar roles. I love sitting with Simera, listening to her listen to her own words to carve out rhythm and shape meaning. Because I don’t often write on my own, having her support in the face of uncertainty helps me fill the blank page, even when the writing comes out ridiculous.

Assuage

SIMERA LADSON

Ctrl + B means never giving up, even when you feel like there’s nothing more. It means you fight.

Dear Simera,

You’ll make it. The days seem long, nights even longer, your inability to breathe will lift. You’ll never imagine where we are now; you’re graduating soon and you don’t look in the mirror and want to die. You and I both know that wasn’t meant metaphorically; you want to die and I look back still understanding why. But I’ve made it this far, meaning we made it this far.

Five days from now, on January 17, 2017, you’ll get into a big argument with your sister, stemming from a tedious debacle on sharing your bed, your discomfort with someone else staying in your room while you deal with trauma. Things will be said that neither of you meant but that you refuse to take back. You will hurt. She will call you ungrateful and blame you for the stress of your mother. She will tell you that your mom will die, and when she does, you cannot cry. With bass in her voice, pins on her tongue, she will say that any sister would be better than you. It will feel like too much. They will see you on the floor, arms bloody, and they will not ask what happened. You will feel the loneliest you have in a long time from the last time. Your body will shake, you’ll be numb, and the skin under your nails will tell you it’s time to go. The urge to die will be at an all-time high, but you won’t. You’ll type out all you should’ve said that no one would’ve listened to, telling your best friends you love them and all the things you guys have been through—telling them how much you cherish them. This will be written in a haze, eyes emotionless, lids swelled and your skin under your nails. You blanked but felt every part, experienced every tear; the rip and snap of your paper bag skin. Tears will fall, colliding with the cold bathroom floor and your laptop will close. You have written out and meant that you should’ve never been born, that it should’ve worked the first time, that this life will never serve you. You’ll look back at your experiences and feel the bad has continued to outweigh the good. You’ll tell yourself there is nothing here for you, that there will always be distress.

But I’m here. I’m here to tell you not of everything turning perfect or seemingly having all your problems vanish, but of pain that hurt a little less every day. The betterness. Tell you of the journey of 2018 that you’ll live to see, the beauty you’ll uncover and the thoughts of death that will present themselves less every day. I need you to know your strength, your ability to transform your voice into a movement and accomplish your own goals. There will be times you fail, that you feel damaged, but I’m here to tell you that you’re not beyond repair. So far, we’ve been receiving college acceptances left and right. You did that!!

You stay alive with a purpose of future success and achievements. You’ll stare at yourself and see your beauty continue to shine through more. The band tees and unappealing jeans will find themselves in the back of your closet and you will be rebranded with hip hugging pants, an abundance of skirts, and everything from tube tops to crop tops. Though you will do this all for you, people will see you and comment on this newfound glow, the confidence they notice rising—and in these moments of expression you will feel the most at peace. Even on dim days, you remind yourself that you are powerful and the impact of your being is undeniable. You cannot be re-created, and if you believe it, then it’s so.

Love, Simera

A girl who promises to never feel small again

Dearest

CAROLINE SYDNEY

Inspired by Simera’s letter to a past self, I decided to reflect on my erratic tradition of writing letters to future selves. Ctrl + B is this persistent return to hopes, promises, and especially to ambition.

The idea of the “five-year plan” exists in my psyche somewhere between an anxiety and a joke. But since middle school, I’ve cast letters into the future for distant selves without ever thinking of them as plans, and then opening them to find just that. When I sit down to write these notes, I envision time capsules of emotions and unanswered questions. But I often read them and find stark goalposts instead.

I am not trying to tell things to my future self; I want things from her. Concrete things like straight A’s and a boyfriend at first, but also more subjective things, like meaningful friendships and good decisions. In these moments before I fold the paper and lick shut the envelope, am I planning? I’ve never thought so. Planning is what I do in my planner. Planning is what I do when I make a to-do list. Planning is what I do before going to the grocery store on a Sunday night, so I know what I’ll make for the week ahead.

For big things, for accomplishments, I thought, I put my head down and worked hard. But in these letters, sealed and filed away, I disguised a road map as a wish. Ambition for me is both of these things: an undercurrent that runs almost hidden beneath the day to day, but also the effort itself.

JADE LOZADA

YEARS AS MENTEE: 2

GRADE: Junior

HIGH SCHOOL: High School of American Studies at Lehman College

BORN: New York, NY

LIVES: New York, NY

PUBLICATIONS AND RECOGNITIONS: National Gold Medal in Journalism, Scholastic Art & Writing Award: Second Place, Columbia Political Review High School Essay Contest, published in Affinity magazine

MENTEE’S ANECDOTE: With Carol, I am always brainstorming. This year she has helped me experiment in new genres, explore themes from last year more deeply in personal essays, and plan new projects. Each piece reveals a part of myself that

I didn’t acknowledge, let alone understand, before sitting down to write. No matter what ends up on the page, Carol values what I have to say and refines my thoughts for everyone else to hear. I am so excited to see what comes next.

CAROL HYMOWITZ

YEARS AS MENTOR: 2

OCCUPATION: Freelance Journalist, Author, and Fellow at Stanford Center on Longevity

BORN: New York, NY

LIVES: New York, NY

PUBLICATIONS AND RECOGNITIONS: Published in The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg Businessweek

MENTOR’S ANECDOTE: Jade’s talent and wisdom shine at each of our meetings, and I continue to be grateful to Girls Write Now for the chance to work with and get to know my mentee. I’m inspired by Jade’s talent and how she writes so well in a range of genres, from short stories, fantasy, and poetry to essays and reported pieces. She keeps growing as a writer as she delves into deep and complex topics. Spending time with her is always a high point of my week.

Learning to Be Myself

JADE LOZADA

Last year, I wrote about the exclusivity of being an American from the perspective of a minority group. This year, I wrote about the sacrifices that I made to fit into that label, and how I reconciled my Latina and American backgrounds to embrace an identity that truly embodies America.

In my sophomore year of high school I learned, through a grammar exercise in my Spanish class, that Puerto Rican women were victims of a secret American medical experiment. The architects of the experiment, including scientists, pharmaceutical corporations, and birth-control advocate Margaret Sanger, marked Puerto Ricans as undesirable for their growing population and rampant poverty. Under a policy that required hysterectomies after the birth of their second child, a third of women were forcibly sterilized. Others were unknowing subjects of a clinical trial of Enovid, an American birth-control pill. At the program’s start in 1955, my Puerto Rican grandmother was seventeen years old and an ideal candidate for a eugenics program.

“This really happened?” I asked my teacher. Since I was a child, the words “guinea pig” had floated through my home whenever Puerto Rico was mentioned. “That’s why the Dominican Republic is better,” my mother would joke. “That’s why you can’t trust these corporations,” my grandmother would warn. But the story was always blurry, the details lost in their retelling. I was always doubtful that the program that they alluded to could have been so large and systematic. In Spanish class that day, I was in disbelief.

“Yes, it did,” said my teacher. “They may have also been the subjects of cancer experiments, but that’s not as certain.” I was oddly impressed; a grammar exercise had taught me something more relevant to my heritage than any history class ever had. Our curriculum never stretched past the Second World War, to the arrival of the immigrants whom I knew. We only broached Puerto Rico insofar as a Spanish colony turned U.S. territory in 1898. Puerto Ricans have been Americans for more than a century but until my Spanish teacher, no one bothered to mention them again. As I considered this, I realized that I had never questioned that reality before. I accepted that history was not my own. In fact, I embraced it. I adored the idea that I was born into a nation with power. If there is one thing that my history classes had taught me, it was that power mattered.

When my global history class finally reached the Latin America unit a few months later, I found myself uncomfortable. I disliked seeing people who looked like me on the projector, because I felt exposed by the thought of my white peers scrutinizing the actions of Latino historical figures. These people fought and died for the independence and power that their colonizers possessed, only for their people to flee their countries and place themselves at the mercy of the United States a century later. I had not anticipated embarrassment, and I blamed myself for my shame. But as I contemplated my feelings, I recognized that they were the product of a long education in a single perspective. This education, which I had always endorsed as the best I could receive, limited my sense of belonging within my own community. I understood the plight of millions of white Americans better than I understood that of my own ancestors, but this fact did not drive me to find a community with my white peers, either. I felt isolated from both groups in my life, stuck in the middle and unable to balance the two to define myself.

I examined my life—my friends, my school, even my parents—and found that I loved nearly every aspect of it individually, just not as a whole. These parts of my life seemed incompatible because there was no link between them. When I returned to Spanish class the following week, I realized that this language was the link that I’d until now rejected. I thought that learning Spanish was irrelevant to who I had become, without appreciating that it gifted me a fluidity between cultures. Looking at my Spanish teacher, I saw that ability in him. He did not sacrifice intelligence, eloquence, nor even power when he stood in front of our class. Belonging to two cultures did not diminish his identity in either, so it should not have to with mine. Yet I knew that he, and all the Latinos whom I had met, never expected me to embrace that. I resolved to try. Thus, Spanish class became a struggle to believe in my legitimacy.

I waited for a eureka moment when my identity would click together. I imagined that it would come in a conversation with my grandparents or my peers. I considered that it might arrive in a wave of contentment as I danced. It did neither. I had been learning Spanish since the seventh grade, but, for the first time, I cared. On the weekends, I pestered my parents to speak with me in Spanish. I watched television series, movies, and YouTube videos in Spanish. I had my first real conversations with my grandparents about my life and theirs. However, I could not muster the courage to speak up in class. I never raised my hand, and I avoided speaking Spanish in class whenever I could. I was in an advanced course, so all my classmates were Latino, too, but most were native speakers. They spoke with all of the confidence and none of the effort. They understood the references and slang that appeared in the videos that we watched in class. Under their gaze, I felt inadequate.

Before that grammar exercise landed on my desk, I thought I could only be important as an American, not as a Latina. When I understood that the two were synonymous, identity materialized as confidence. I did not have to prove that second-generation is just as Hispanic as first-generation any longer, because I felt in my heart that it is. To be further along in the journey of an immigrant family does not absolve you of obstacles as I had wanted to believe. All those years, I was not in the same category as my white peers. By discrediting my experience, I was denying who I am. Learning Spanish revealed that I shared the spirit of a community that I chose to neglect. Yet accepting that community compensated for the fragments of empathy lost to a white education.

Learning to Be Older

CAROL HYMOWITZ

Ageism is rife in our culture, and especially the workforce, even as growing numbers of men and women want to continue working in their sixties and beyond. In this essay, I explore this theme and how I and many others are challenged by ageism—sometimes by trying to pass for younger.

I lower my voice to a whisper when I call my internist from my desk at work. I’m in an open office, three feet from the person next to me and the one behind me. It’s not that I care if they overhear me describe how I hurt when I pee and likely have a urinary tract infection. It’s my birth date I don’t want them knowing, and which I’ll have to provide to get an appointment.

I feel like the office crone. I’m a memory bank about good and bad bosses and assignments, whose advice about pay and job moves colleagues now younger than my daughter seek. But for all the counsel I dole out, I’m scrambling to keep up with tweegrams, Skype and other technology and social media they navigate so easily.

So much I do know dates me. I joined the workforce when help-wanted ads were gender-segregated into “men wanted” and “women wanted” lists, when becoming a “gal Friday”—a secretary with a college degree who was willing to fetch coffee for the boss and smile when handing him the cup—was my b

est chance for a job. Women, or “girls,” as even middle-aged females were called, were forbidden to wear pants to work. Nylons and heels were required every day. Dress-down Fridays didn’t exist.

It took me five years before I broke out of the secretarial pool in publishing and another four to go beyond proofreading and become a newspaper reporter. Even then, in 1979, I was the sole woman in the bureau where I worked, one of only about two dozen at a national paper that employed hundreds.

No one can accuse me of being sexist, after all the feminist marches I’ve joined, pro-choice petitions I’ve signed, and women I’ve hired. And I wouldn’t likely ever be judged anti-Semitic. I’ve kept my identifiably Jewish name when I could have easily traded it, as one editor urged me to do, for the much shorter WASP name of my first husband.

But I’ve internalized ageism. I’m in hiding, trying to pass for younger than I am. I don’t want to be considered “outmoded,” “hoary,” “antiquated,” or any of the other synonyms for “old” that pop up when I check my thesaurus. Why should I be ashamed of my age? I ask myself. After all, I’m one of a huge cohort. Ten thousand Americans are turning sixty-five every day and will continue to do so for the next fifteen years. And my generation isn’t aging quietly.

We wrote, spoke, and sang about how we were transforming politics, sex, and marriage in our teens and twenties. Now we’re sprouting books, blogs, podcasts, and conferences about how we’ll age with more verve, boldness, and grace than anyone who was ever old before us.

Every day, I read about another baby boomer accomplishing a feat they didn’t or couldn’t do when they were younger. Diana Nyad swam 110 miles from Cuba to Florida at sixty-four—her fifth try. “You’re never too old to chase your dream,” she said when she emerged from the ocean after fifty-three hours.

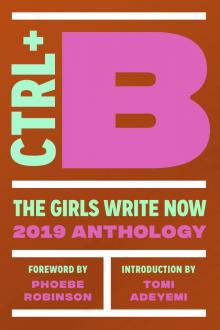

Ctrl + B

Ctrl + B